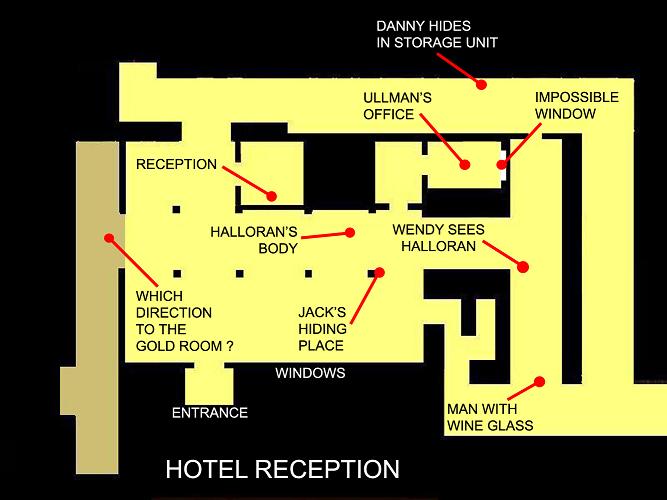

The Shining

Impossible space 1:

Impossible space 2:

The Shining

Impossible space 1:

Impossible space 2:

Final exam study guide

Evaluations

Experimenting with the Materiality of the Film Medium

abstraction: pure “form” liberated from “content” >> the materiality of the form’s medium comes to the foreground

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)

Free Radicals (Len Lye, 1958/1979)

Mothlight (Stan Brakhage, 1963)

Outer Space (Peter Tscherkassky, 1999)

Source material:

Hallucination, Illusion, Perceptual Modulation

“materiality” here comes to mean the materiality of the viewer’s perceiving body

The Flicker (Tony Conrad, 1965)

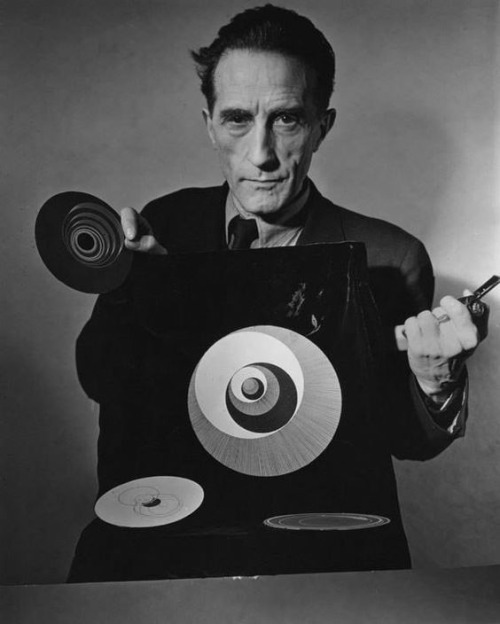

Anemic Cinema (Marcel Duchamp, 1926)

Rotoreliefs: two-dimensional discs that create an illusion of depth

T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (Paul Sharits, 1968)

Experimental sound-image relations and “visual music”

Color organs:

Wassily Kandinsky, “Composition VIII” (1923)

An Optical Poem (Oskar Fischinger, 1938)

Synchromy (Norman McLaren, 1971)

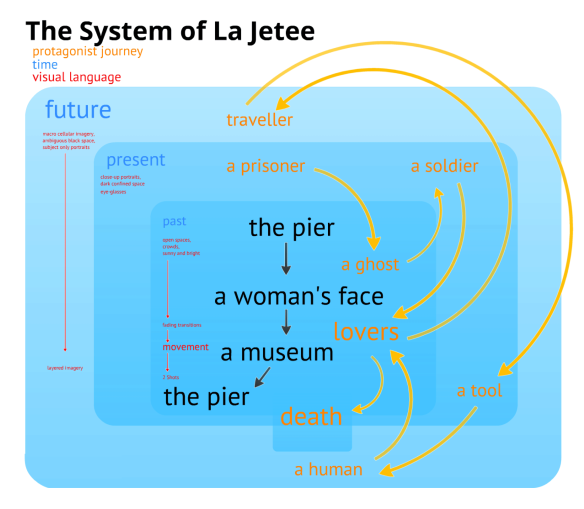

La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

Terms to keep in mind / things to attend to as you watch:

fabula

syuzhet

all terms pertaining to sound

animation (is this an animated film or a live-action film? if it is animation, what kind of animation is it?)

Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren, 1943)

Terms to keep in mind:

fabula and syuzhet

our two “match” cuts (eyeline match, match-on-action) and the concept of continuity editing more generally

Note the schedule change (plus “extended office hours” session)

Screening for today:

Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (dir. Jacques Tati, France, 1953)

Buster Keaton

Charlie Chaplin

Jackass

What’s going on here? Why do we laugh? What theory of laughter can we develop as a means for understanding the viewer’s reaction to the above clips? What is laughter’s ontology in this context?

abjection

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror

“Food loathing is perhaps the most elementary and most archaic form of abjection. When the eyes see or the lips touch that skin on the surface of milk—harmless, thin as a sheet of cigarette paper, pitiful as a nail paring—I experience a gagging sensation and, still farther down, spasms in the stomach, the belly; and all the organs shrivel up the body, provoke tears and bile, increase heartbeat, cause forehead and hands to perspire.”

Hence the ages-old proscription against eating with one’s mouth open.

Abjection is interesting because it blurs the lines between genres, especially between horror and comedy:

Kristeva: “laughing is a way of placing or displacing abjection” (Powers of Horror, 8).

Degrees of abjection (social rather than visceral/physical)

Genre and abjection on election night (comedy becoming documentary becoming horror in real time):

First, before we get into the screening: final paper instructions

It Follows

“To sum up: both the plasticity of the image and the resources of editing have endowed cinema with a broad arsenal of techniques for imposing on viewers an interpretation of the event being depicted” (Andre Bazin, “The Evolution of Film Language,”90).

Video Player

Horror

The major questions we’ll consider:

Another way of framing these questions is to keep the following passage from Bazin’s “The Evolution of Film Language” in mind:

“To sum up: both the plasticity of the image and the resources of editing have endowed cinema with a broad arsenal of techniques for imposing on viewers an interpretation of the event being depicted” (Andre Bazin, “The Evolution of Film Language,”90).

Remember that “plasticity” refers to all of those manipulable elements of mise-en-scene: decor, set design, make-up, costume, lighting, and blocking (which refers to the positioning of the actors in front of the camera)

Pre-history of the horror film:

Stage shows and magic theatre:

German Expressionist film:

1930s-1950s: An emphasis on the monster’s body and mise-en-scene (the plasticity of make-up and costume design)

1960s-1990s:

Interesting counter-example (victim’s body is the monster’s body):

The Exorcist (1973)

2000-present: Two major tendencies in contemporary American horror film: “torture porn” and found-footage films (not the only tendencies, but the main ones)

Animation

Stop-motion animation (pages 136 and G-7): A variation on drawn animation techniques that uses puppets or other three-dimensional objects. To give the appearance of life on film when projected at the normal 24-frames-per-second speed, subjects are moved minimally between shots as they are being photographed.

Hand-drawn animation (not in textbook): Animation in which each frame is drawn by hand and then photographed. To give the appearance of life on film when projected at the normal 24-frames-per-second speed, each subsequent drawing depicts a small change in position.

Cel animation (not in textbook): a technique used for hand-drawn animation in which characters are drawn and painted on sheets of clear celluloid (or “cels”). The cels are placed over a separate background image and photographed one by one. The advantage of this technique is that it cuts down on the amount of drawing involved, since you don’t need to redraw the background in each frame.

Computer-generated images, or CGI (pages 134 and G-2): Visual images that are created exclusively by computer commands rather than by standard live photography or stop-motion animation. This method has been widely used in many types of films, but only during the 1990s did entirely CGI features such as Toy Story and A Bug’s Life appear.

Top: Toy Story 2 (1999) Bottom: Toy Story 3 (2010)

Andre Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” pp. 7-8:

Photography’s originality compared to painting thus lies in its objective nature; in French the lenses of the photographic eye are called, precisely,obectifs. For the first time, the only thing to come between an object and its representation is another object. For the first time, an image of the outside world takes shape automatically, without creative human intervention, following a strict determinism. The photographer’s personality is at work only in the selection, orientation and pedagogical approach to the phenomenon: as evident as this personality may be in the final product, it is not present in the same way as a painter’s. All art is founded upon human agency, but in photography alone can we celebrate its absence. Photography has an effect upon us of a natural phenomenon, like a flower or snowflake whose beauty is inseparable from its earthly origin.

The automatic way in which photographs are produced has radically transformed the psychology of the image. Photography’s objectivity confers upon it a degree of credibility absent from any painting. Whatever the objections of our critical faculties, we are obliged to believe in the existence of the object represented: it truly is re-presented, made present in time and space. Photography transfers reality from the object depicted to its reproduction. The most faithful drawing can give us more information about the model, but it will never, no matter what our critical faculties tell us, possess the irrational power of photography, in which we believe without reservation.

So why does all this matter?

http://www.cbc.ca/news/trending/paris-attacks-canadian-sikh-selfie-photoshop-1.3320327

Another case study: the ubiquitous lens flare

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media

What happens to cinema’s indexical identity if it is now possible to generate photorealistic scenes entirely in a computer using 3-D computer animation; to modify individual frames or whole scenes with the help a digital paint program; to cut, bend, stretch and stitch digitized film images into something which has perfect photographic credibility, although it was never actually filmed?

Manovich’s answer:

Consequently, cinema can no longer be clearly distinguished from animation. It is no longer an indexical media technology but, rather, a subgenre of painting.

Part 1

Part 2

“By added value I mean the expressive and informative value with which a sound enriches a given image so as to create the definite impression, in the immediate or remembered experience one has of it, that this information or expression ‘naturally’ comes from what is seen and is already contained in the image itself. Added value is what gives the (eminently incorrect) impression that sound is unnecessary, that sound merely duplicates a meaning which in reality it brings about” (Michel Chion, Audio-Vision, 5)

(clip from Stagecoach)

Mickey Mousing (pages 252 and G-5): The exact, calculated dovetailing of music and action that precisely matches the rhythm of the music with the natural rhythms of the objects moving on the screen.

Animated example:

Live-action examples:

Peter-and-the-Wolfing (pages 257 and G-6): Musical scoring in which certain musical instruments or melodies represent and signal the presence of certain characters. Basically synonymous with the term leitmotif (page G-4), the repetition of a single musical theme to announce the reappearance of a certain character.

Another, subtler example (again from Stagecoach):

Generalized score aka implicit score (pages 253 and G-3): A musical score that attempts to capture the overall emotional atmosphere of a sequence and the film as a whole, usually by using rhythmic and emotive variations on only a few recurring motifs.

(aka what Michel Chion calls “empathetic music“)

Music can also be anempathetic…

Examples:

The Public Enemy

Little Big Man

Another interesting case study is the musical genre: